The tight linkage between chip designs and chip manufacturing processes has caused its share of havoc in the IT sector, and it is getting worse as Moore’s Law has slowed and Dennard scaling died a decade ago. Wringing more performance out of devices while trying to keep a lid on power draw is causing loads of trouble as chip makers try to advance the state of the art. When there are failures to meet chip process targets set by the foundries of the world, chips drive off the roadmap page and smash on the floor.

Nothing demonstrates this better than Intel’s own issues with bringing a 10 nanometer chip etching process to market in the past five years, which has allowed room for AMD to re-enter the server CPU market with gusto and which has kept Intel from being as aggressive with GPU and FPGA accelerators as it might have otherwise been. But Intel has been far from the only disappointment, apparently.

Publicly, IBM seemed to shrug off disappointments with former foundry partner GlobalFoundries, which was supposed to take over the delivery of 14 nanometer technologies for IBM Power and z processors and deliver 10 nanometer and smaller chip etching techniques as part of a ten-year agreement inked in October 2014 and closed in July 2015. Under that agreement, IBM essentially gave GlobalFoundries its Microelectronics division, which made all kinds of processors, including those for Sony, Microsoft, and Nintendo game consoles as well as IBM’s server CPUs and a slew of chippery for all kinds of customers, including the US government. As it turns out, IBM did shrug off the delays in getting 14 nanometer chips out of the fabs – our observation is that they were about a year late with Power8 – but IBM has apparently been seething for years about the spiking of the 10 nanometer process, which the public did not know about unless they connected some dots, and then the spiking of the 7 nanometer process, which was done abruptly in August 2018. This left Big Blue without a server roadmap, essentially. And now, IBM wants at least $2.5 billion in damages.

The lawsuit, filed in the New York Supreme Court on June 8, has not yet been made public on that court’s systems, but we got our hands on a heavily redacted version and you can download the PDF file here. The GlobalFoundries response, which came out before anyone was aware of the IBM lawsuit and a day before IBM filed the lawsuit, has been made public and can be found at this link.

This situation is messy for IBM and GlobalFoundries: technically, economically, and emotionally. But if the things that IBM is alleging in its lawsuit are true, then this will be a textbook case of how a foundry partnership can go bad.

The most obvious question is: Why is IBM doing this now? It has been almost six years since GlobalFoundries pulled the plug in its 10 nanometer efforts, and nearly three years since it pulled the plug on 7 nanometer processes and even smaller transistor shrinks. But as IBM is winding down its Power9 and System z15 servers and is no longer as dependent on GlobalFoundries as it has been in prior years – the company picked Samsung Electronics as its foundry partner in the wake of the GlobalFoundries spike and is etching its future Power10 and z16 CPUs using the Korean chip maker’s 7 nanometer processes – Big Blue has decided it wants satisfaction.

The timing is a bit suspect, particularly with rumors swirling around about Mubadala Investment Company, the investment arm of the oil producing nation of Abu Dhabi and the owner of GlobalFoundries, getting ready to file an initial public offering this year on a stock market in the United States. That IPO is projected to be worth $20 billion to $30 billion, thanks in large part to the semiconductor shortage that IBM cannot benefit from because it has not been a foundry since July 2015.

Coincidence is a real thing in the world, and it is probably a coincidence that a worldwide shortage in semiconductor manufacturing – on advanced nodes or old ones – is what is helping to make GlobalFoundries valuable just as IBM probably has all the wafers it needs to fulfill Power9 and z15 orders forever. That’s why it is happening now. As for why it is happening at all, that’s a much more complex situation, and it is important to remember that claims and counter claims in lawsuits are not facts until a jury and judge determines them to be so – and maybe not even then.

IBM GETS OUT OF THE FOUNDRY BUSINESS

Back in 2013 and 2014, IBM was in one of the divesting moods it periodically gets into. It sold off its System x X86 server business to Lenovo and “sold” the Microelectronics division to GlobalFoundries, which itself was spun out of AMD in October 2008 and previously augmented with the chip making business Chartered Semiconductor. All three of these chip businesses together, plus a research and development agreement with IBM and its other partners at the Center for Semiconductor Research at the State University of New York’s Albany NanoTech Complex. These days, both Samsung and now Intel are contributing to and benefiting from that research, presumably including IBM’s breakthrough 2 nanometer chip processes announced last month. The first 7 nanometer and then the first 5 nanometer CPUs in the world were etched there, so this is practical research that helps foundries get chip done.

As part of the Microelectronics deal, GlobalFoundries got itself a portfolio of around 16,000 patents and patent applications, which is an important shield against litigious rivals, as well as two mostly outdated foundries – one in East Fishkill, New York and the other in Essex Junction, Vermont – and around 5,000 employees who design chips and run foundries. Big Blue kept a small team of people to design its Power and z processors and some of the people at IBM Research working on semiconductors. IBM agreed to pay GlobalFoundries $1.5 billion over three years to invest in 14 nanometer and 10 nanometer processes and took another $3.2 billion in writeoffs. In 2013, Microelectronics had $1.4 billion in sales, but had a pre-tax loss of $700 million, so you can understand why Big Blue wanted out. Every new process shrink was going to be increasingly painful and increasingly expensive and IBM just did not have the kind of scale that GlobalFoundries had hoped to build. IBM’s lawsuit contends that GlobalFoundries was not capable of building “high performance” chips, which is ludicrous given that AMD was perfectly capable of building market-leading Opteron CPUs for servers and Radeon GPUs for graphics and visualization long before this deal was done.

What is fair to say is that GlobalFoundries needed to keep the AMD business and adding IBM’s business to it would help it snowball CPU, GPU, and other accelerator business to better take on Intel, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Corp, and Samsung for client and server parts and other ASIC manufacturing and packaging. IBM’s foundries were not really useful for the future, but the money and the people certainly were. In fact, Thomas Caulfield, the current chief executive officer at GlobalFoundries, ran the Fab8 foundry built by GlobalFoundries and ran the East Fishkill foundry at IBM from 1989 through 2005 before dabbling in venture capital and startups for a while before joining GlobalFoundries.

The crux of IBM’s lawsuit is that GlobalFoundries promised to deliver 10 nanometer processes and then changed it to 7 nanometer processes – and did neither. To hedge its bets, GlobalFoundries took a twin path to 7 nanometers, one using standard immersion lithography and another using extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography. The latter is a technique that TSMC got right first, Samsung is perfecting now, Intel is working on and has had some issues, and GlobalFoundries did not follow through with at the 7 nanometer node. GlobalFoundries presumably killed its 7 nanometer efforts because it already knew that AMD was going to TSMC for at least some of the chips inside the “Rome” Epyc 7002 and “Milan” Epyc 7003 server processor packages. We know that AMD decided to skip over the 10 nanometer node, which may have also played into the decision by GlobalFoundries to not invest in it even though its contract with IBM explicitly said it would do just that. Without the relatively high volumes of AMD server chips, IBM’s server chips would not have paid the bills on the immense investment. We don’t know what the numbers are, but the same math held true at Microelectronics when IBM decided to get rid of it.

What we don’t know is if AMD decided to jump over 10 nanometer processes to 7 nanometer processes to get an edge on Intel or if it really had no choice to do so because GlobalFoundries was pulling the plug to focus on its dual-prong 7 nanometer effort. We think AMD was hit by the same 10 nanometer surprise that IBM was, but AMD never said anything about that and put the best spin on it. Much as IBM did with the difficulties that GlobalFoundries apparently had bringing 14 nanometer processes and IBM never said much at all about 10 nanometer issues. AMD, of course, used 14 nanometer processes from GlobalFoundries for its first generation “Naples” Epyc 7001 chips and still uses 14 nanometer processes in the I/O and memory hub at the heart of the Rome and Milan server processor packages. The Rome and Milan cores are etched by TSMC in 7 nanometers, and Infinity Fabric links hook hub and the cores together in a single package.

The delay with the 14 nanometer processes and the stoppage of 10 nanometer processes is evident in the IBM Power roadmaps. Take a look at this Power processor roadmap from a few years ago:

Saying that Power9 shipped in 2017 is generous, since it was only low volumes of CPUs for the “Summit” supercomputer at Oak Ridge National Laboratory and the “Sierra” supercomputer at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. It took IBM all of 2018 to fully ramp systems based on the Power9 chip that was etched using GlobalFoundries 14 nanometer processes.

We can’t prove this, but we think the original plan from IBM was to shrink to 10 nanometers with Power10 and create a dual-chip module chiplet to push it up to 48 cores. We also think IBM definitely wanted to get this out the door in 2020 and keep on the three-year cadence it likes with its server platforms. IBM says that the first rumblings that the 10 nanometer process was in trouble came in September 2015, only two months after the Microelectronics deal was inked, and by December 2015, GlobalFoundries said it would not do it. IBM alleges “upon information and belief” that GlobalFoundries knew it was going to do this before the deal closed.

IBM says it never released GlobalFoundries from the 10 nanometer commitment, but worked “in good faith” on the development of a 7 nanometer chip. This, we presume, was the shift we now see from a Power10 based on 24-core chiplets to a Power10 with a radically new core with 16 physical cores per chip but 15 or 30 fat or skinny cores per chiplet and 30 or 60 cores per package – the one that Samsung is currently slated to manufacture later this year for Big Blue:

According to IBM’s suit, GlobalFoundries said in the fall of 2016 that it would have a 7 nanometer test chip ready in the second quarter of 2017, pilot production in the first quarter of 2018, and volume production in the third quarter of 2018, and alleges further that “GlobalFoundries repeatedly represented to IBM that the 7nm chip GlobalFoundries would develop would be an adequate substitute for the 10nm chip it had promised.”

Given this, IBM cut the check for the last $250 million traunch in the $1.5 billion in cash it promised as part of the Microelectronics division transfer, and says that through 2017, it had invested at least $188 million in resources to help GlobalFoundries in this 7 nanometer effort. At this time, GlobalFoundries was ramping the 14 nanometer technologies used with the Power9 and z13 chips – which Big Blue says “was subject to significant delays and issues regarding performance and quality” – and Caulfield, who was made CEO in July 2018, allegedly told IBM that it might go through with 7 nanometer development if IBM paid an additional $1.5 billion. By August, IBM demanded that GlobalFoundries return the $1.5 billion, which the chip maker balked at, obviously, and by the end of the month GlobalFoundries publicly announced it was suspending its 7 nanometer efforts, including both water immersion and EUV lithography techniques and would focus on 14 nanometer and older technologies.

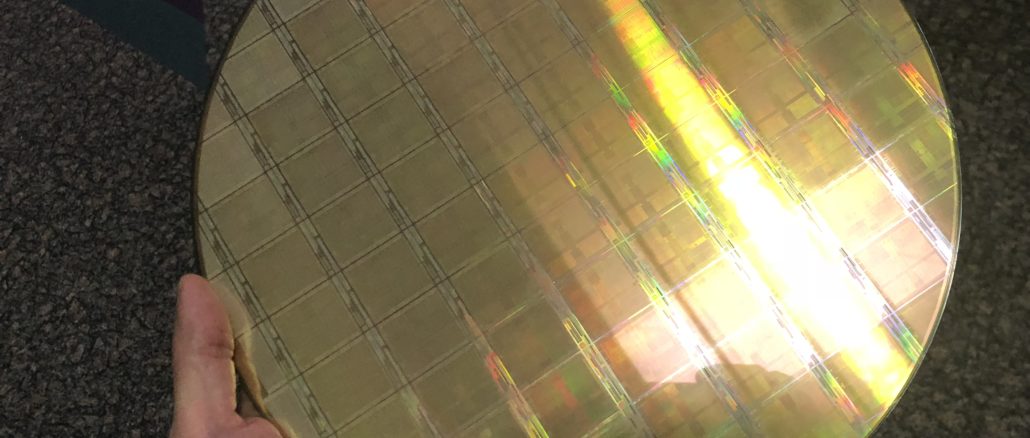

While the two companies were bickering back and forth about what their agreement meant and whether or not it had been breached, GlobalFoundries sold off the East Fishkill fab to ON Semiconductor for $430 million in April 2019 and sold its custom ASIC business to Marvell in May 2019 for $650 million with an additional $90 million potentially coming in, and then sold off some other assets that IBM says tally up to $1 billion and which basically ensured that GlobalFoundries could not make good on its 10 nanometer legal commitments and 7 nanometer promises. This is a stretch. The 7 nanometer stuff was done in the Fab8 factory in Malta, New York. We have seen it with our own eyes. IBM can’t transfer assets as part of a deal and then get mad when the “buyer” decides to sell.

IBM can certainly be upset, and seek economic damages, if GlobalFoundries promised chip fabbing and didn’t deliver. The case is hard to make with 14 nanometers, since chips did get out even if later than expected as seems to be the case, but it is easy to make with the 10 nanometer and 7 nanometer spikes. These definitely caused IBM to rewrite its Power and System z processor roadmaps and definitely caused delays in deliveries of advanced technology. We have no idea how much all of this change undermined IBM’s bids for the successor “Frontier” exascale system at Oak Ridge or the “El Capitan” exascale system at Lawrence Livermore, but it could not have helped. (We think a lot of other factors were at play there.)

Still, lawsuits are about recovering economic damage. It will be hard for a jury to do the math on what it might be, but adding the $1.5 billion that IBM gave GlobalFoundries as part of the Microelectronics transfer and then the $1 billion or so that GlobalFoundries got from selling off assets together is not a sufficient method to calculate the economic damage in this case.

We wanted to get some sort of commentary out of IBM, but given this is a lawsuit, what we got was this statement from an IBM spokesperson: “IBM depended on GlobalFoundries after investing heavily in a long-term mutual relationship. GlobalFoundries responded by taking IBM’s money, and benefitting from IBM’s knowledge, skill and assets. Though GlobalFoundries repeatedly assured IBM that it would meet its commitments, GlobalFoundries instead abruptly and without any justification walked away from IBM while IBM was reliant on GlobalFoundries. GlobalFoundries has demonstrably failed to act as a reliable partner and supplier.”

“YOU CAN FIND BETTER, BUT YOU CAN’T PAY MORE*”

GlobalFoundries, in its response, is unequivocal about the situation. “This action arises out of what seems to be a misguided and ill-conceived effort by IBM’s law department to try to extract an outlandish payment from GF that IBM knows it is not entitled to,” its legal response starts. “IBM’s timing is not only highly suspect as it comes on the heels of recently reported news of a potential initial public offering (“IPO”) by GF that would value it at approximately $30 billion, but also incredibly inconsiderate of current events, namely a global chip shortage fueled by a pandemic that has impacted important domestic industries, including the automotive sector.”

GlobalFoundries says that it spent the $1.5 billion IBM gave it investing in the foundry business, and then spent “far more than this amount” itself further investing. While this is a provable and calculable figure, it was not given in the response. GlobalFoundries also alleges that IBM mutually agreed to forego the 10 nanometer node and purse the 7 nanometer node. But given “the technical complexity and enormous financial cost” of the 7 nanometer effort, GlobalFoundries could not deliver 7 nanometers on the timeline set. (We think at a cost that GlobalFoundries would or could bear as well.) Given that others had 7 nanometer techniques, GlobalFoundries “opted not to place itself in serious financial stress through the continued pursuit of a failing strategy and accordingly ceased developing 7nm technology,” and “IBM quickly found a new, and less expensive, 7nm technology supplier in Samsung.” IBM, GlobalFoundries contends, actually benefitted from GF’s decision to cease working on 7 nanometer technology.

IBM might have gotten to 7 nanometers quicker this way, but it sure could have used Power10 a year or more ago based on 10 nanometer technology. IBM doesn’t say that in its filing, but we are saying that. And if there is any economic damage, that’s it. System z customers are not itching for capacity in the same way. But the HPC market, and particularly hybrid CPU-GPU machines where the CPU has lots of I/O and memory bandwidth, and maybe a memory area network as Power10 has, surely could have already used those Power10 processors. Maybe it might have been selected in the DGX-2 system, in fact. This has to be part of any calculation of economic damage, if any is to be made.

This lawsuit by IBM is not frivolous, perhaps, but it certainly is opportunistic and disruptive to GlobalFoundries. But if it does proceed to trial, the damages will not be anywhere close to the public float of GlobalFoundries stock, and the chip maker will take the hit and maybe even get on with developing more advanced processes as a foundry of its stature and heritage should.

*Note: Famous quote from an IT manager in the Wall Street Journal in the 1990s talking about an IBM that was struggling.